EPA Posts Ebola Claim Guidance

Today, EPA posted Ebola claims guidance to its Antimicrobial Policy and Guidance Documents Webpage.

At this time, the Agency is not allowing label claims related to antimicrobial product efficacy specifically against the Ebola virus. However, if a product meets CDC guidelines for Ebola virus disinfection, companies can identify such products on websites and through other non-label marketing.

In order to meet CDC guidelines, the product must bear at least one label claim for a non-enveloped virus. Examples of common non-enveloped viruses follow:

Norovirus; hepatitis A virus; rotavirus; adenovirus; poliovirus; parvovirus; rhinovirus; various enteroviruses.

Though not stated by EPA in the guidance, Antimicrobial Test Laboratories believes that products should also be approved for use in hospitals, because the CDC document describes only “hospital disinfectants” and addresses disinfection within the hospital environment. Hospital disinfectants are those effective against both Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Note about EPA guidance: As guidance, the document is not binding; EPA may depart from it where circumstances warrant, without prior notice. Pesticide registrants and applicants may propose alternatives to the recommendations described in the guidance, and the Agency will assess them for appropriateness on a case-by-case basis.

Ebola Epidemic Grows and Spreads

Antimicrobial Test laboratories last updated its clients on the ongoing West African Ebola outbreak on August 25, 2014. At that time, the outbreak had infected approximately 2,615 people in Africa and caused about 1,427 deaths.

Just two months later on October 25, the World Health Organization (WHO) reports 12,008 suspected cases and 5,078 deaths.

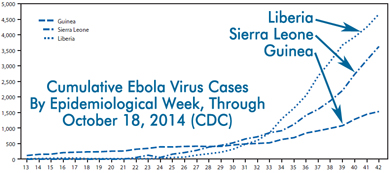

In Africa, Ebola virus spreads at a rate of approximately two new infections for each old infection, resulting in exponential growth, as shown below (data through October 18, CDC).

Recent data, from epidemiological weeks 38-42, suggests the rate of new cases is decreasing. Under-reporting of illness may be responsible for this apparent decline. In any case, the spread rate must be held below “one” for a long period of time in order to stop the outbreak.

Perspective: Ebola’s Long Tail

By Benjamin Tanner, Ph.D.

By Benjamin Tanner, Ph.D.

As a microbiologist specializing in infectious disease control by antimicrobial intervention, I have been fascinated by the outbreak in West Africa. I marveled at the virus’ exponential propagation, was skeptical of official assurances that it cannot spread in the West, and felt relief when recent data from real US cases confirmed that Ebola virus was not easily spread by surfaces.

It has been wonderful to see the lab’s customers rise to the challenge. Products and devices made by ATL customers disinfected the Texas hospital where Thomas Duncan died, helping prevent the Ebola virus from getting a Dallas toehold. Clients have also donated disinfectants to West Africa to aid in their fight against the outbreak.

What concerns me now is the long tail of Ebola virus. In statistics, a “long tail” refers to a distribution with an unusually great number of low-likelihood occurrences. A high-likelihood occurrence would be another infected person coming to the United States from West Africa. A low-likelihood occurrence would be that person vomiting on a crowded New York City subway car, or a terrorist intentionally infecting themselves to spread the virus. Some low-likelihood occurrences have catastrophic outcomes.

Viruses evolve rapidly and their reproductive prospects are determined by the behavior, biology, and inter-connection of the entire human population. That kind of complexity means that nobody really knows what Ebola’s statistical tail looks like. I suspect, however, that it is longer than we appreciate. I think every new case in Africa makes unlikely Western scenarios proportionately more likely. We should all work to fight the Ebola virus outbreak in Africa, and not be cavalier when Ebola infections come again to the West.